How did the game get to become so complicated? Where did the golf industry go awry?

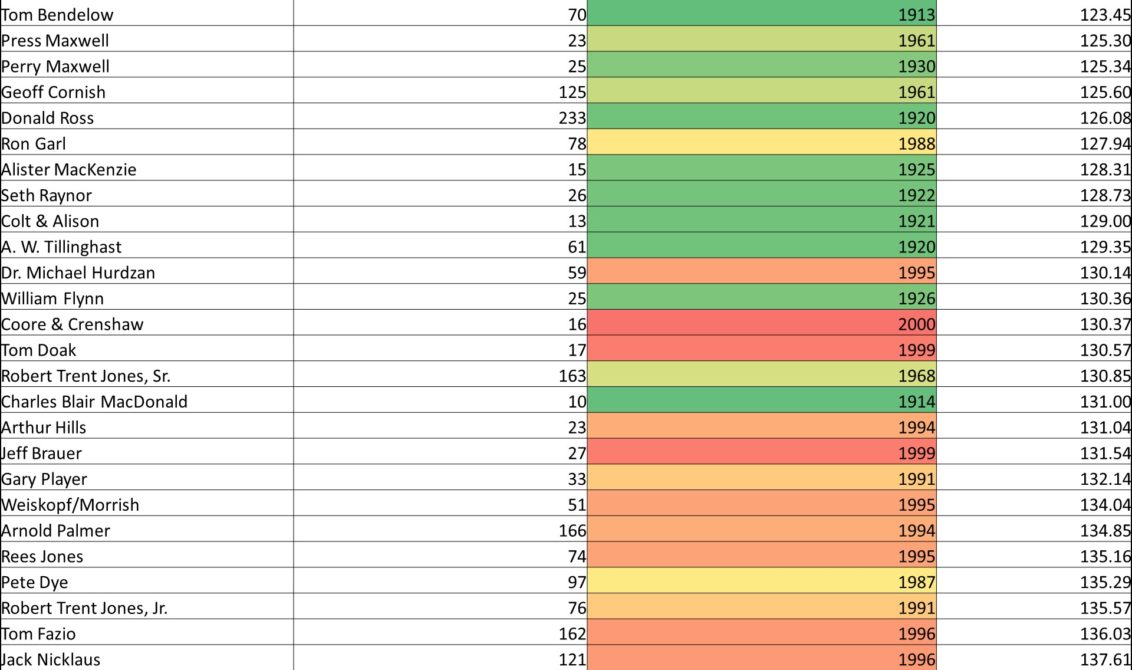

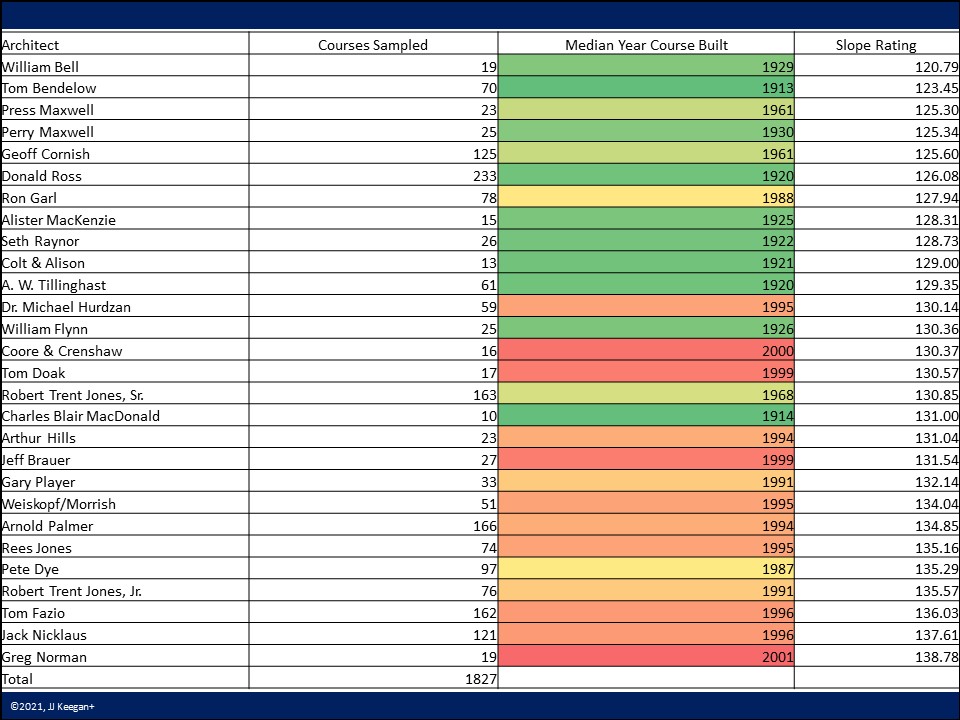

I believe it was at the hands of today’s modern architects: Robert Trent Jones, Pete Dye, Jack Nicklaus, Tom Doak, early in his career David McLay Kidd, and many others. With the increase in popularity of golf lead by Arnold Palmer, ‘bigger and better’ became in vogue as the U.S. grew in affluence. It is fascinating to see the influence of the famed architects on the increasing difficulty of the game, as shown here:

It is important to understand the difference between the course rating and slope rating.

The course rating is:

“A USGA Course Rating is the evaluation of the playing difficulty of a course for scratch golfers under normal course and weather conditions. It is expressed as the number of strokes taken to one decimal place (72.5), and is based on yardage and other obstacles to the extent that they affect the scoring difficulty of the scratch golfer.”

The slope rating is:

“The USGA slope rating of a golf course is a mark that describes the measure of difficulty for a bogey golfer relative to a scratch golfer at a specific set of tees. It describes the fact that when playing on a more difficult course, the scores of higher-handicapped players will rise more quickly than those of lower handicapped golfers. The slope rating of a set of tees predicts the straight-line rise in anticipated score versus USGA course handicap, as in the mathematical slope of a graph.”

The lowest slope rating is 55, and the highest is 155.12

Note that the above chart, which focuses on slope rating, comes with a million caveats. We believe it fairly states “in all significant and material respects,” the slope rating for each architect. But we are sure it does not precisely measure the slope rating from the back tees of all courses built by the named architect. Why?

First, not all golf courses built by an architect were sampled. The sample range highlighted the courses from 1870 to 2013. Thus, if a course, i.e., a Donald Ross masterpiece, was subsequently renovated by another architect, it was not considered. Ross built over 400 golf courses, but only his courses in the United States were studied.

The slope rating for some courses, i.e., Sand Hills in Nebraska, a Top 10 Golf Course in the world, is surprisingly not listed in the USGA Slope Rating database as of January 2020. Some of the best courses built by Coore & Crenshaw and Tom Doak after 2013, i.e., Sand Valley in Wisconsin, are not included. We are confident, had they been, the slope rating of Doak’s courses would reflect a higher rating.

Golf Course architects are like artists. Their canvas is the earth. Their paint brushes are bulldozers. From its inception, golf was a ground game. The introduction of the aerial game by Robert Trent Jones Sr., the devilish British Brutes by Pete Dye, which brought forced carries to the fore. False fronts and small green targets by Nicklaus were the forks in the road that has contributed, along with changes in equipment perceived as making historic courses obsolete, to the industry’s decline.

Difficult became celebrated as the slope rating of golf courses increased from the average of 120 before 1980 to 127 after that. The courses they built were without concern about the cost of maintenance or other operational considerations. They defend their Machiavellian practices, meekly stating they were merely fulfilling the wishes of those who retained them. Other architects became enamored and built courses on steroids, amplifying their egos. They catered to a small group of elitist and highly skilled golfers. Or, they used their ability as a basis for their designs, continuing to make the game too challenging and not much fun for the masses. In fairness, we noted that not all, but many architects have played a role in making the courses too difficult.

To obtain independent verification about the increasing difficulty of the game, we asked Joseph Passov, former long-standing Travel Editor for Golf Magazine, for his reaction to our research about architects and escalating slope ratings. A historian of the game of comparable stature to the incomparable Bradley Klein, prolific author, and highly respected architectural critic, Passov replied:

“This is certainly an interesting premise. I think you’ve got a sufficient number of primary/influential architects represented. At least from an anecdotal standpoint, the data seems correct.

“I’m a little surprised that Weiskopf/Morrish is as ‘high’ as it is, because they were more into playability, especially compared to the Nicklaus (and Fazio and Dye) courses that always seemed in their neighborhood, but it’s not ridiculously high, either. Coore-Crenshaw has never been all about difficulty, so I’m not surprised to see the trend towards the lower end of the slope scale. I forgot how hard Norman’s courses could be, given that he’s generally favored that short cut around his mostly low-profile greens, but I guess as a group, his tracks are tough.

“My gut feeling about those high average slopes and what brutally hard courses did to harm the game is complicated.

“Nicklaus, Fazio, Dye, Jones Jr. built many courses intended to be vehicles to sell real estate. As such, they went with exciting features and many hazards because they looked appealing to real estate buyers. Also, developers knew that they could attract premium buyers by hosting big tournaments and by getting ranked as ‘Top 100’ or ‘Best New.’

“Well, you attract a big tournament by offering up a ‘tough test.’ And due to Golf Digest’s great emphasis on ‘Resistance to Scoring’ as one of its critical variables in their rankings, developers (and their architects) went the extra mile to create those tough courses. Why build a green with a simple grass knob in front that would prompt all kinds of strategy puzzles when you could prop it up and front it with water and sand? That’s where things went very wrong in terms of playability and fun.

“While the criticism may be true that Jack only built the kinds of courses that fit his own game (at least the bulk of them), the other guys were guilty of building to the whims of the developers who wanted bigger, harder, more dramatic.”

A member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects privately commented: “The average ASGCA member handicap has to be over 10. I’m going to guess it’s closer to 15 since, for every single digit I’ve played with, I know 2 or 3 that can’t hit it out of their shadow. “From my experience, if there is anything to learn from the ASGCA, many do not genuinely understand how the game is played. It takes very little skill or knowledge of the game to make a hard golf course.

“I believe much of our misalignment with golfers is we ignored proven design principles found at places like the Old Course and the National Golf Links, and thought we could do better, that our ideas of mounds, railroad ties, and deep bunkers were advancing the game, when in fact they were ignoring why we love the game.

“We love the game for the adventure, the successes of striking a solid shot, the thrill of a saved par from a bunker, and the camaraderie.

“Fortunately, compelling short courses and well-thought-out practice fields like wedge ranges are becoming in vogue.”

Another ASGCA member commented:

“I do think there has been a monumental shift in the mentality of many architects who grew up in the age of declining golf participation. There are a whole bunch of guys that seem to understand how to make golf fun, but, for some reason, the ‘the old guard’ still doesn’t seem to get it.

“They talk the talk but continue to build new courses and remodel existing courses and incorporate multiple forced carries and bunkers that are excessively penal. “David McClay Kidd had an ‘aha moment,’ and now he seems to embrace the importance of width, large greens, etc. His earlier works were very penal. Many architects are outstanding golfers, and I believe they don’t truly understand how far the average person hits the ball or how little control they have over where it goes.

“I also contend that frequently we in the golf business (architects, golf pros, managers, Board members, and Greens Chairman) don’t understand that the average golfer is not the high handicap golfer at his club (maybe a 15 or 20 handicap) but rather the ‘average golfer’ is the guy who doesn’t belong to a country club and doesn’t have a USGA handicap and maybe only plays 3-5 times a year.

“I think my wife would fall into that group. She played 4 or 5 times last year, doesn’t have a handicap, hasn’t bought clubs in 5 years, and couldn’t care less what her score is. She’s out there for the fun of it (and dinner afterward).

“If one in seven people plays golf, it seems that only a small percentage of those people probably consider themselves a ‘golfer.’ If, as an industry, we could figure out how to get those other six people to try the game a few times a year, that

would be huge for growing the game.”

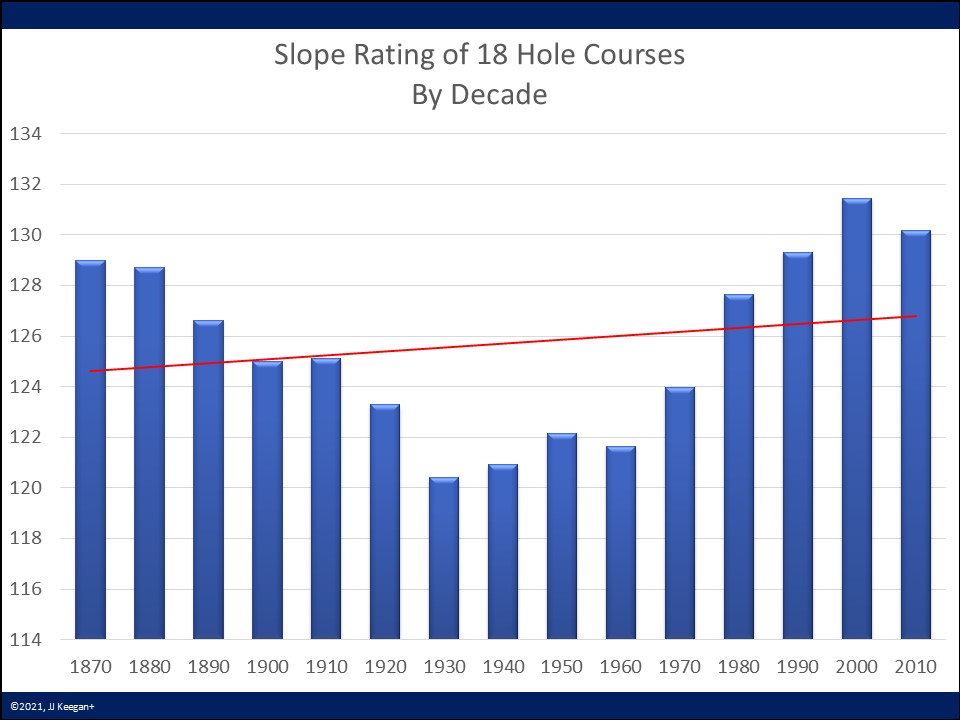

Shown here is a summary of the slope rating of courses in the United States by decade, which further confirms that golf has gotten too difficult for the masses:

Why the dip from 1920 to 1960? From World War I, the Depression, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, one could speculate those events consumed resources and attention, rendering the construction of golf courses more expensive. Shorter + Easier = Lower Construction Costs, all things being equal. The higher the slope rating, the greater the maintenance costs, and the longer the pace of play, which impacts the customer experience and the ability of the golfer drawn to the facility.

Ultimately, we believe there is a correlation between the slope rating and the green fee that should be charged to cover the increased maintenance costs. One should multiple the maintenance budget, including salaries, by 0.0001 to determine if your green fee prices are properly set.

Author: James J. Keegan, Envisioning Strategist, and Reality Mentor. His sixth book, “The Winning Playbook for Golf Courses: Shorts-Cuts for Long-Term Financial Success,” was released on June 20, 2020, Click Here. Keegan was named one of the Top 10 Golf Consultants and Golf Advisor of the Year in 2017 by Golf, Inc. Keegan has traveled more than 2,996,000 miles on United Airlines, visiting over 250 courses annually and meeting with owners and key management personnel at more than 6,000 courses in 58 countries.

© 2021, JJKeegan+

lawrence w doyle

Very interesting analysis. I have been in the golf ownership business for 29 years and I have observed that some of the most successful local market courses in our area are the ones that were the easiest to score on. One in particular was built in 1962 by Geofrey Cornish. It has unusually large greens (for its age) without a lot of elevation changes and the bunkers are set back quite a distance from the greens. Looking at the holes from the tee the course looks difficult and beautiful but it is very forgiving to play.

JJ Keegan

Geoffrey Cornish, who I had the pleasure of meeting when asked what his favorite designed course was, commented, “Every course is like a son and a daughter. You love them all equally.” The philosophy you espoused in your comment was very comparable to Brian Whitcomb’s philosophy in building Lost Tracks in Bend, Oregon. Appreciate you taking a moment to comment. Writing is a lonely sport.

JJ Keegan

Geofrey Cornish, who I had the pleasure of meeting, when asked what his favorite designed course was, commented, “Every course is like a son and a daughter.” You love them all equally. The philosophy you espoused in your comment was very comparable to Brian Whitcomb’s philosophy in building Lost Tracks in Bend, Oregon. Appreciate you taking a moment to comment. Writing is a lonely sport.