The Philosophy of Green Design

In the ongoing dialogue about golf course architecture, the design of greens remains one of the most defining elements of play. They are the stage upon which strategy, artistry, and fairness converge. Yet, not all greens achieve this balance.

Tom Doak’s work, while admired for its creativity, often leans toward excessive undulation. The movement across his surfaces can be visually dramatic, but it requires a lower stimpmeter rating to remain playable. In practice, these contours diminish the importance of precision iron play, as the ball’s resting point is dictated more by terrain than by shot-making. Similarly, many contemporary architects allow their greens to wander without clear intent. At the same time, Donald Ross’s steeply tilted back-to-front designs, though iconic, can prove overly severe, producing an abundance of tricky side-hill putts.

For me, the ideal green responds thoughtfully to the length of the approach shot. Michael Stranz, in the eight courses he completed, and Jay Morrish, in many of his designs, embodied a philosophy that I believe strikes the right balance. On longer par 3s and par 4s, a generous runway allows the ball to settle naturally, ensuring that golfers who do not hit a towering shot are still given a fair chance. On shorter par 3s and 4s, as well as par 5s, the introduction of shelves—gentle slopes of three to five degrees that connect to flatter portions of the putting surface—creates distinct zones of play. Typically encompassing a quarter to a third of the green, these shelves reward precise iron shots with manageable putts, while punishing imprecision with the risk of a three-putt.

When such structuring is combined with features like a Biarritz or a punchbowl, the result is a collection of greens that are not only strategically demanding but also deeply engaging. They invite variety, challenge, and creativity, offering golfers a richer and more rewarding experience.

Ultimately, the best greens are not those that overwhelm with movement or severity, but those that harmonize with the shot required to reach them. They elevate the game by rewarding skill, offering fairness, and creating memorable moments. In this way, green design becomes more than a technical exercise—it becomes the art of shaping opportunity.

Thus, will AI replace golf course architects to achieve the right balance?

We have a client who is building a new course in their portfolio. They are contemplating designing the greens using AI and featuring that as a marketing brand to attract and retain golfers. Their idea is compelling.

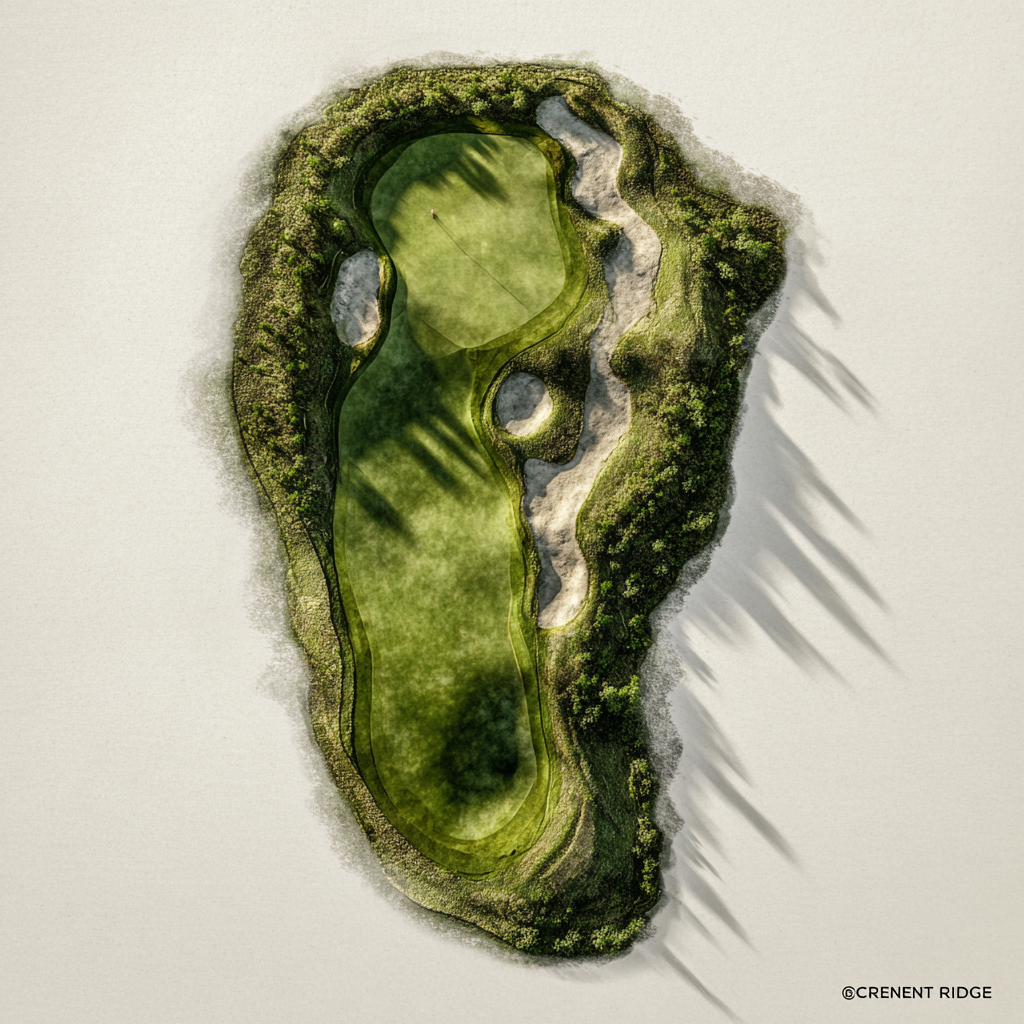

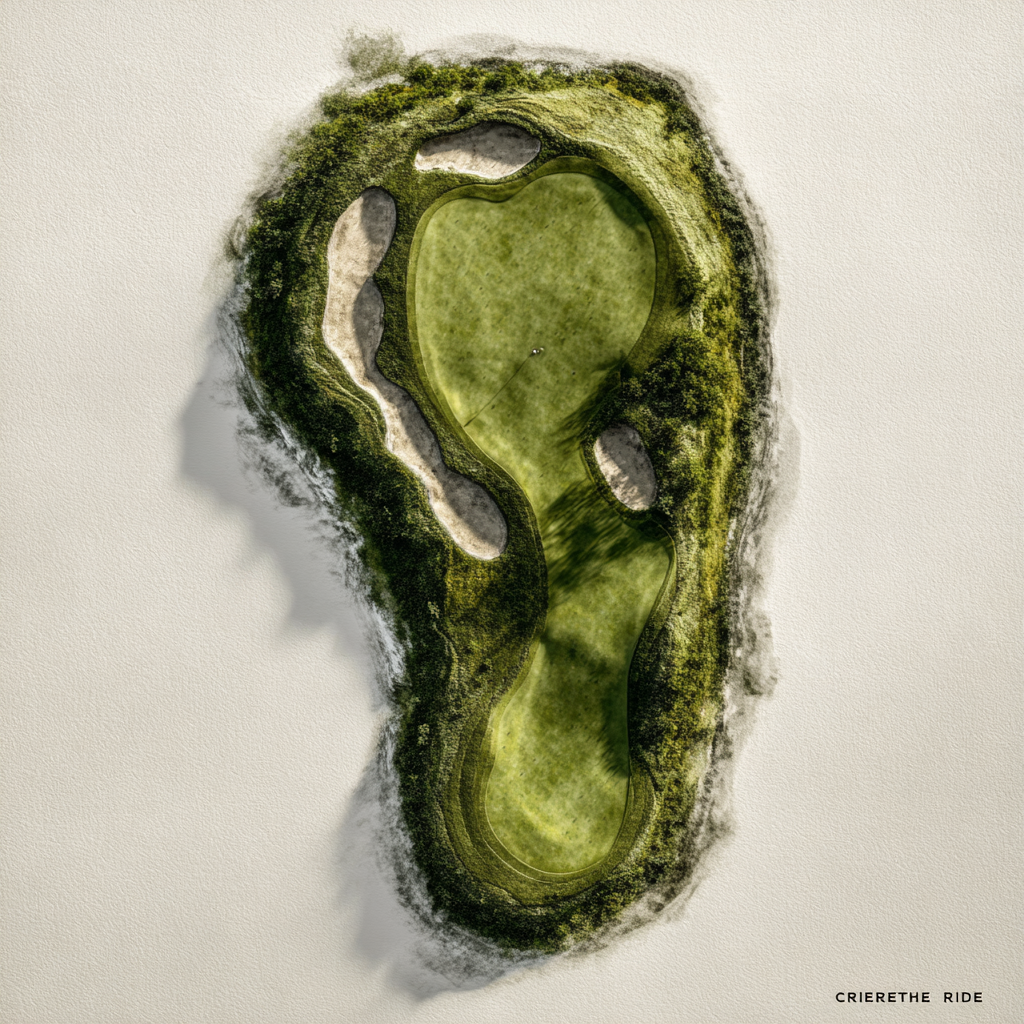

Shown below are three green complexes created by AI based on their preferences:

Simply fascinating. While the concepts would require a talented shaper to build, it makes one wonder if the role of the golf course architect will be reduced based on AI.

The pace of play is directly influenced by the speed of the greens, affecting both the golfer’s enjoyment and, ultimately, the financial success of the golf course.

Will AI be used to create the perfect balance of interesting green complexes that optimize the speed of play?

What are your thoughts? Please comment.

Kevin Norby

Great article JJ. Although these are interesting looking par 3 drawings, I don’t believe Ai can take into account the more intangible design elements like safety, routing the course to take advantage of natural site features/landforms and making holes playable for a wide range of golfers. I see Ai as a tool that architects might use to prepare presentation drawings. I’d be skeptical if Ai would be of much benefit preparing the detailed drawings that contractors need to bid and build a golf hole. Routing the course or designing the hole on paper is just a small part of the design process. Somebody still needs to determine, bunker placement, size & orientation as well as cart path routing, fairway width, grass species selection and root zone composition.